Greetings, all! Sorry it’s been a while; teaching @ Halstrom (my new job) has kept me pretty busy.

Two weeks or so ago, I had a minor revelation about psychology in literature; I will share those thoughts with you now.

Most are familiar with the superego-ego-id imagery presented by the media; we see it portrayed as an argument between “angel” and “devil” personalities. The superego always urges us to do the “right thing” as determined by a higher sense of right and wrong, while the id encourages instant fulfillment of immediate, basic desires. The ego listens to both voices and ultimately determines which one will win and thus influence the choices made on their advice.

A prime example of this pattern is in the Disney film, “The Emperor’s New Groove”:

Kronk is debating whether or not to save Kuzco from a deadly plunge over a waterfall; he serves as the ego, or core personality, while the Shoulder Angel and Shoulder Devil represent the superego and id, respectively.

In a way, the relationship is similar to a monarch and their advisers.

However, as history notes, the monarch may be strong or weak, and in the psychological sense, a weak monarch/ego is open to bad suggestions from an adviser with ulterior motives (the id).

This imagery is more subtlety shown in other media, both written and visual.

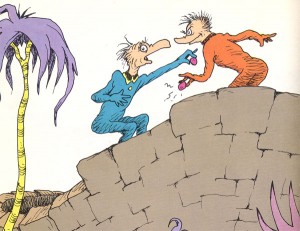

Those who are familiar with Dr. Seuss will readily understand this next comparison:

In “The Cat in the Hat” story, the Cat represents the wild/crazy id, the Fish represents the proper/strict superego, and the two children are the ego who make choices based on the influence of each side.

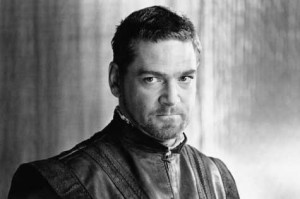

One of the most famous (and tragic) examples is in Robert Louis Stevenson’s masterpiece “The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde”:

Part of the tragedy is that Jekyll loses control of Hyde, and eventually he becomes Hyde permanently. However, let us take a closer look at the relationship between the two.

Stevenson, speaking as Dr. Gabriel Utterson, one of Jekyll’s friends, walks us through Jekyll’s account of his transformation. Utterson serves as the superego, while Jekyll himself is the ego and Hyde, obviously, is the id. The trouble is, Henry Jekyll fails to recognize his own divided nature, instead identifying himself and Hyde as “good” and “evil” twins.

It is only later that he seems to address his error, by which point it is too late. Jekyll admits that other people are repulsed by Hyde because, unlike others (who are a mixture of “good” and “evil”), Hyde is pure evil. By failing to see this, Hyde’s dominance of Jekyll slowly advances until Henry Jekyll must take his formula to remain himself. When it runs out, he becomes Hyde permanently.

Another famous book that is more subtle displaying the psychological relationship was written by children’s author Roald Dahl.

In the Chocolate Factory, Charlie is the ego, the parents and Wonka himself are the superego, and the other four children (Augustus, Violet, Veruca, and Mike) are the id. As the book progresses, the four “id” characters are removed one by one as they proceed to immediately satisfy each of their desires despite ample warning from the superego characters.

The final example is from the dystopian novel, “Lord of the Flies.” The movie brings out the imagery in a more recognizable manner.

Ralph, on the far left, is the ego; he adapts to life on the island (wearing fewer clothes, searching for food, etc.), but tries to maintain some sense of order. Behind him, Piggy (the fat boy) serves as the superego, reminding the boys that their behavior is slipping away from the societal norm. On the far right stands Jack, the head choir boy who quickly leads the others into savagery; his actions show that he represents the id – stealing Piggy’s glasses to make fire, leading hunts rather than build a signal fire or shelters, and finally initiating a wild rampage of war that destroys the island.

In each example, we see the conflict between opposing sides of the mind; ultimately, the ego is responsible – and held accountable – for the decision made. A key quote from King Baldwin IV in “The Kingdom of Heaven” exemplifies this:

“A king may move a man, a father may claim a son, but that man can also move himself, and only then does that man truly begin his own game. Remember that howsoever you are played or by whom, your soul is in your keeping alone, even though those who presume to play you be kings or men of power. When you stand before God, you cannot say, ‘But I was told by others to do thus,’ or that virtue was not convenient at the time. This will not suffice. Remember that.”